What Wind Load Really Means for Residential Fences (And Why Most Fail)

Most people hear “wind-rated” and picture a single number: wind speed. But wind damage isn’t caused by “speed” in the abstract. It’s caused by pressure acting on area, gusts that spike loads, and how an entire fence system moves and transfers force into the ground.

If you’re a homeowner, designer, or builder, the goal isn’t to memorize engineering equations. It’s to learn the handful of concepts that separate a fence that stays put from a fence that becomes a repair project after the first serious wind event.

Fast skim: the 60-second wind-load primer

- Wind load is force, not a weather headline. In practice, wind creates pressure on the windward face and suction (negative pressure) on the leeward side. Even simple references note that suction effects are commonly estimated for leeward/side faces. (rds.oeb.ca)

- Gusts matter because they create short-duration peaks (the “maximum instantaneous” wind) that often govern failure. (National Weather Service)

- Area multiplies everything: a taller/wider, more solid panel simply “catches” more load.

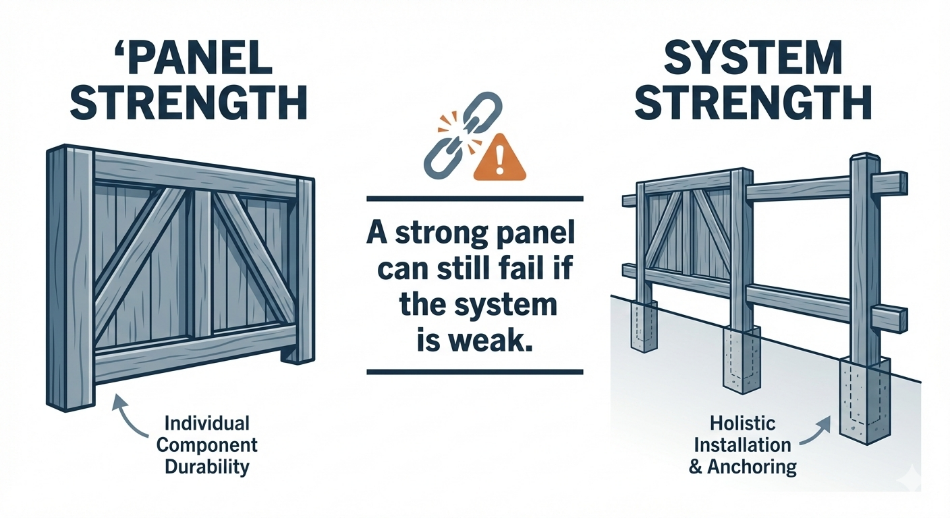

- A fence is only as strong as its system: posts + rails + fasteners + foundations + spacing + geometry.

- Permeable/slatted fences behave differently than solid privacy walls because they let some air pass through, often reducing overall pressure, while changing where stresses concentrate.

Wind load: pressure, suction, gusts (not just “wind speed”)

Weather apps report wind in terms of speed, but structures “feel” wind as pressure (force per area). A basic way to see the relationship is the common rule-of-thumb formula:

wind pressure (psf) ≈ 0.00256 × V² (V in mph)

That same source explicitly highlights the key takeaway: pressure rises with the square of wind speed, so it ramps up fast.

A simple “why speed alone misleads” table (rule-of-thumb)

Using the formula above (for intuition, not design), pressure ramps quickly:

|

Wind speed (mph) |

Approx. dynamic pressure (psf) |

Approx. dynamic pressure (kPa) |

|

40 |

4.10 |

0.20 |

|

60 |

9.22 |

0.44 |

|

80 |

16.38 |

0.78 |

|

100 |

25.60 |

1.23 |

The jump from 50 → 100 mph is not “double the load.” It’s about four times the pressure. (rds.oeb.ca)

Gusts vs sustained wind: which number matters?

- Sustained wind (NWS) is an average over time (NWS glossary describes it as a two-minute average). (National Weather Service)

- A wind gust (NWS) is the maximum instantaneous wind speed during rapid fluctuations. (National Weather Service)

For fences, those “instantaneous” peaks can be the moments that:

- pop fasteners,

- drive slats into excessive deflection,

- or push a post past its elastic limit (after which it never quite returns straight).

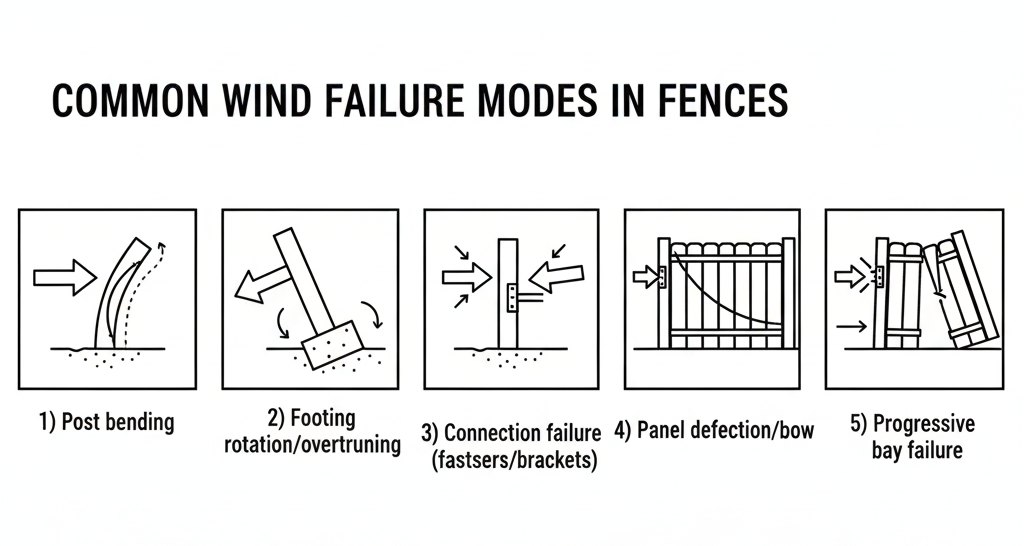

Why fences fail in wind events: the common weak links

Wind failures tend to look sudden, but they’re usually the end of a predictable chain. Below are the most common mechanical failure modes, what breaks, and why.

Failure mode map (scannable)

|

What fails |

What it looks like |

Why it happens (mechanism) |

What “engineered” designs address |

|

Post bending |

Whole bay leans; “S” bend near base |

Post behaves like a cantilever; bending moment grows with height + load |

Larger/stronger posts, correct spacing, verified capacity, robust base/footing |

|

Footing / embedment failure |

Post rotates at ground; soil cracks |

Overturning exceeds soil/footing resistance |

Minimum footing depth/diameter, base plate/anchors (if surface mount), soil considerations |

|

Fastener pull-out / shear |

Rails detach; screws rip out |

Peak loads concentrate at connections |

Better connection geometry, more fasteners, tested assemblies, controlled tolerances |

|

Rail failure |

Top/bottom rail bows; slats loosen |

Rails carry panel loads to posts; weak rail = weak system |

Reinforced rails; tested rail capacity |

|

Panel/slat deflection |

Visible bowing; slats pop or rattle |

Deflection increases stress at edges and joints; cyclic loading loosens interfaces |

Stiffer slats, reinforcing profiles, controlled span |

|

Progressive bay collapse |

One bay fails, then others follow |

Once one bay opens, loads redistribute and spike locally |

Redundancy, strong end/corner conditions, clear install rules |

Panel strength vs system strength (the mistake most buyers make)

A common marketing move is to talk about “strong panels,” but wind doesn’t load “a panel in isolation.” Wind loads travel:

slats → rails → post connections → posts → anchors/footings → soil or slab

So you need two different questions:

1) Is the panel stiff/strong enough?

That’s about slat geometry, reinforcement, and span.

2) Is the system strong enough?

That’s about posts, rail-to-post connections, anchors, and foundation conditions.

A system-level approach is exactly what shows up in properly documented test programs: multiple tests addressing different load paths.

Example (documentation style): In an Ontario Building Code compliance engineering letter for PrimeAlux’s slat system when used as a guard/rail, the letter doesn’t only mention one test, it summarizes vertical rail loading, horizontal slat loading, and wind load testing as separate checks, because they stress different parts of the assembly. (PrimeAlux)

Why permeable/slatted systems behave differently than solid panels

A solid privacy fence is closer to a “sail.” A slatted fence introduces porosity, letting some flow through. That tends to:

- Reduce overall pressure on the assembly (less air stagnation on the windward side),

- Change load distribution (more localized loads on slats/rails),

- Reduce suction effects in some conditions (not always, depends on geometry, gaps, and turbulence).

Even a basic wind-load overview notes that designers often consider suction from pressure differentials on sidewalls and leeward faces, fences experience the same “push/pull” pattern, just at smaller scale. (rds.oeb.ca)

Practical takeaway

If you want privacy and wind resilience, slatted designs can be a smart direction, but only if the system (posts, rails, connections, footing) is engineered for the resulting load paths.

What good “wind-rated” evidence looks like (and why it’s rare in residential fencing)

Residential fencing is often sold like finish carpentry: style, color, and “durability” claims, without the kind of documentation you’d expect for a structural building component.

What’s unusual (and useful) is when a manufacturer publishes:

- test method descriptions,

- test results, and

- system specs (post size, rail type, anchors, minimum base requirements).

PrimeAlux as a worked example (supportive, evidence-based)

PrimeAlux is a useful case study because it publishes a set of documents that cover different failure modes:

- Wind load testing (system-level behavior)

An Ontario Building Code compliance letter summarizing the system states that a 6’ × 6’ privacy panel was tested using distributed sandbag loads, and reports a maximum wind velocity resistance of 169.8 km/h (with an “equivalent pressure” noted as ~0.72 kPa).

Why it matters: even if you don’t use the number directly, you can see the configuration (panel size) and the method (distributed loading) instead of a vague “wind-rated” slogan. - Slat load testing (panel behavior + span sensitivity)

PrimeAlux publishes a slat load test document describing horizontal and vertical distributed loading on two slats with a reinforcing profile (H+), across 6’, 5’, and 4’ panel widths. It shows (for example) that maximum distributed load values rise substantially as span decreases.

Why it matters: it demonstrates a fundamental engineering truth buyers rarely see: span controls capacity. If someone sells an 8-foot bay with the same confidence as a 4-foot bay, you should ask how they validated it. - Fire performance testing (third-party lab documentation)

PrimeAlux publishes an Intertek test report for ASTM E84 on the “PrimeAlux Privacy Slat fence system,” including Flame Spread Index and Smoke Developed Index results. The report also includes standard lab caveats: results apply to the specimen tested and are not a certification by themselves.

Why it matters: whether or not you need E84 for a residential fence, third-party test reports signal a seriousness about controlled, repeatable evaluation. - Structural system design disclosures (posts/rails/anchors)

On the product documentation side, PrimeAlux publishes system specs for 80 × 80 mm extruded aluminum posts, top/bottom rails, a base plate bracket with expansion screw anchors, and, in one configuration, a stated minimum concrete thickness under the base plate.

Why it matters: wind failure is often a post, base, and connection problem. Publishing these details makes it easier for designers/builders to assess whether the system fits the site conditions.

A scannable “documentation checklist” table

|

Document type |

What you learn |

Why it helps wind performance decisions |

|

Wind test summary with method |

Panel size, loading approach, reported resistance |

Lets you compare evidence, not slogans |

|

Slat load testing across spans |

How capacity changes with width and reinforcement |

Highlights span sensitivity; avoids overpromising |

|

Third-party fire test report |

Controlled test results + limitations |

Demonstrates lab-based evaluation culture |

|

Published system specs |

Post size, rails, anchors, base requirements |

Connects “panel claims” to real install requirements |

“Most fences fail” because most are sold without system-level questions

A fence fails when one link in the chain is under-designed or poorly installed:

- a post that’s too small for the span,

- anchors not suited to the substrate,

- rails that can’t carry slat loads without excessive deflection,

- connections that loosen under cyclic gusting.

And because gusts are instantaneous peaks (not steady averages), small weaknesses show up fast.

That’s why a strong, defensible position for any manufacturer isn’t “trust us”, it’s:

- Here is the system configuration,

- here is how it was tested,

- here is what the results apply to,

- and here are the installation requirements that make those results meaningful.

PrimeAlux’s publicly posted wind/load/fire documents are notable precisely because they follow that structure more than the typical residential fence pitch does.

What to Ask a Fence Manufacturer About Wind Before You Buy

If you ask only “what wind speed is it rated for,” you’ll often get an answer that’s hard to verify. Better questions focus on pressure, configuration, and load paths:

The buyer’s wind questions (copy/paste)

What exact configuration is the wind claim based on?

Ask: height, bay width, post spacing, orientation, solid vs slatted, and whether corners/ends were included.

Do you have a test report or engineering letter and what method was used?

Look for: how load was applied (e.g., distributed loading) and what size panel was tested.

Is the “rating” about the panel, or the full system (posts + rails + anchors + footing)?

A credible answer distinguishes panel behavior from system behavior.

What are the post and rail specs, and what anchors/footings are required?

If they can’t tell you post size, rail type, and base requirements, they’re not talking about wind in a system sense.

How does span affect capacity?

If the product is sold in multiple widths, ask whether capacity changes across spans and whether they have data.

What are the limitations of the tests?

Good documentation states limitations (specimen tested, not a blanket certification).